The following article, written by Jon Chesto, was first published in the October 2 online edition of The Boston Globe

At first glance, it might seem like a simple courtroom showdown between the MBTA and the Town of Sudbury over an underground power line.

But to the state’s major commercial real estate trade group, the fight that played out at the Supreme Judicial Court on Tuesday is about much more.

NAIOP Massachusetts isn’t a party to the case. But it did weigh in — on the side of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority and utility company Eversource — through a friend-of-the-court brief.

The reason? Should the state’s highest court side with the town, NAOIP worries that transfers of publicly owned properties across the state could grind to a halt.

To get this far in its appeal, the town homed in on the state’s “prior public use doctrine” — a common-law understanding that land already devoted to one public use can’t be changed to a different one without state legislation. A Land Court judge ruled in 2018 that the doctrine didn’t apply in the Sudbury case, because the land would be leased for a private use. The town appealed, and the SJC decided to take up the issue.

George Pucci, a lawyer for Sudbury, argued Tuesday that this is an unusual case, one that would not open the floodgates. He noted that much of the right-of-way had once been acquired by eminent domain for transportation purposes.

But the potential broader impact was on the minds of the justices, as their line of questioning made evident.

NAIOP got involved after the SJC put out a call for input in May. Of particular concern to the trade group: The judges said they wanted to review whether the public-use doctrine should be in effect for transfers of property that would lead to private uses.

That request didn’t come out of left field. Pucci, in his initial appeals brief, argued it wouldn’t make sense to prohibit the transfer to an inconsistent public use while allowing the sale for an inconsistent private use. This, he wrote, would defeat the purpose of the doctrine: to protect public land from being converted to a different use without legislative approval.

Words like those can strike fear in the heart of any developer. Tamara Small, NAIOP’s chief executive, says a mandatory trip to the Legislature would open up a whole new layer of uncertainty and expense for public-private partnerships. Begging on Beacon Hill would bog down the development process, the mere prospect preventing many deals from happening in the first place.

In its brief, NAIOP offered a smattering of examples to emphasize some of these partnerships’ public benefits: an apartment complex in Chinatown with more than two dozen affordable units, clean energy from solar panels that dot state land along the Massachusetts Turnpike and other highways, the pending Polar Park stadium that will be built on city-owned property for the soon-to-be Worcester Red Sox.

What about Eversource? What public benefits would the electric utility offer with its deal? The company says its 9-mile Sudbury-to-Hudson line, mostly in a rail corridor, would bring nearly $9.4 million in lease payments to the T over 20 years. The line would help improve grid reliability in Greater Boston, with a side benefit of allowing a rail trail to be built along the stretch.

To the Sudbury town officials who authorized the litigation, these benefits don’t seem worth the adverse environmental impacts, such as damage to wetlands and wildlife habitats along the corridor.

Jessica Gray Kelly, NAIOP’s lawyer, says her client is agnostic on the fate of that project. But the association’s members do worry that the effects could ripple far and wide if the court decides legislative approval is needed for any change of use in a public property deal, not just for those in which control would be transferred to another public agency.

It would be a new world for real estate development in the state. Kelly demurs when asked how she thinks the court will react. But NAIOP’s insertion into this seemingly local fight shows the trade group is not taking any chances.

You can find NAIOP’s Amicus Brief and more information about the case by clicking here.

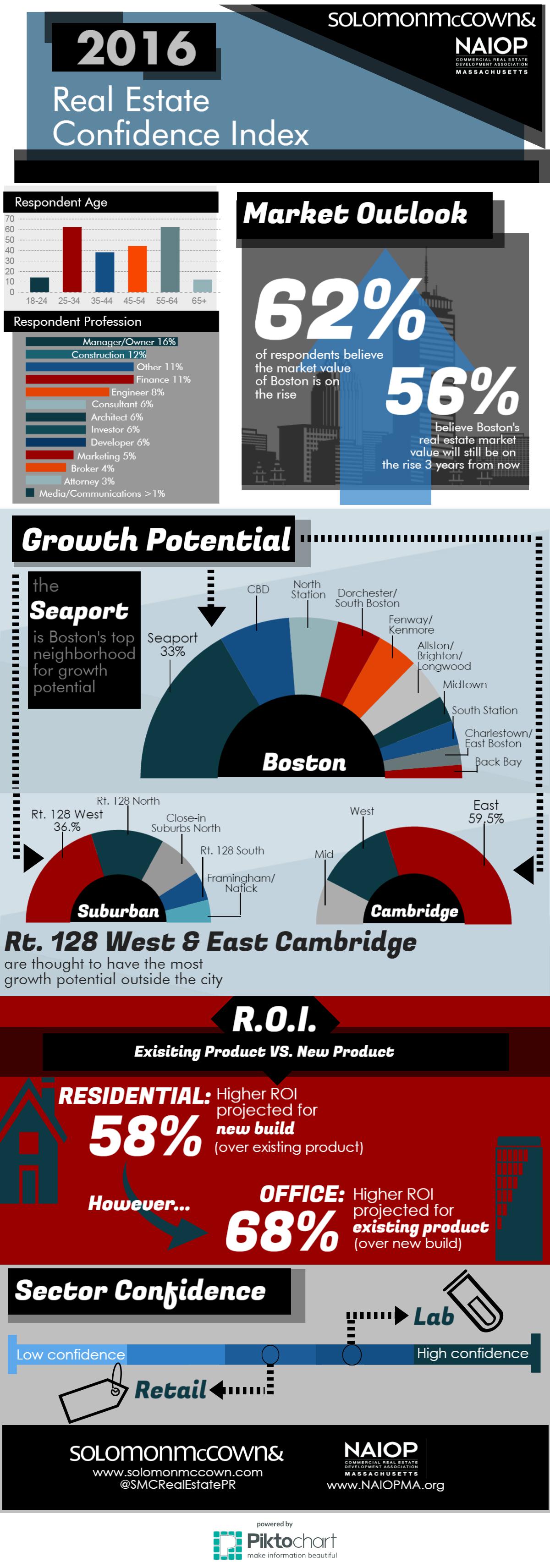

Fueled by one of the strongest economies in the nation, the Boston commercial real estate market should continue to thrive for the foreseeable future. That was the conclusion of the enthusiastic panel at the 2017 NAIOP/SIOR Annual Market Forecast held last week at the Westin Waterfront Hotel before a crowd of 450 CRE professionals.

Fueled by one of the strongest economies in the nation, the Boston commercial real estate market should continue to thrive for the foreseeable future. That was the conclusion of the enthusiastic panel at the 2017 NAIOP/SIOR Annual Market Forecast held last week at the Westin Waterfront Hotel before a crowd of 450 CRE professionals. But despite the positive outlook, there is a looming threat to the overall health of Greater Boston economy, he cautioned. “The housing stock is limited and growing too slowly to meet the demand, and as a result, home prices and rents continue to rise,” said Bluestone, who is one of the co-authors of the

But despite the positive outlook, there is a looming threat to the overall health of Greater Boston economy, he cautioned. “The housing stock is limited and growing too slowly to meet the demand, and as a result, home prices and rents continue to rise,” said Bluestone, who is one of the co-authors of the  JLL’s Heath led off the program with an overview of the Cambridge office and lab markets. “The Cambridge market is one of the strongest markets that we track globally at JLL, and it continues to be driven by this incredible demand from the tech and life science clusters,” she stated, adding that the demand is coming not only from organically grown companies, but outside firms seeking to establish an R&D presence in close proximity to

JLL’s Heath led off the program with an overview of the Cambridge office and lab markets. “The Cambridge market is one of the strongest markets that we track globally at JLL, and it continues to be driven by this incredible demand from the tech and life science clusters,” she stated, adding that the demand is coming not only from organically grown companies, but outside firms seeking to establish an R&D presence in close proximity to  Colliers’ Carroll reported that “the suburbs are alive and well”, as the market has added over five million SF of positive absorption since the downturn. There has also been a steady increase in rent growth in the Class A office market, approximately 10 percent since 2009, with new construction in Waltham achieving rents in the low $50s. The Class B market is not faring as well (although there is some rent growth occurring in select markets), with some of the older building stock being slated for repositioning or demolition to make way for senior living, hotel and other non-office uses (including 450,000 SF of properties in Chelmsford). One particularly bright spot is the emergence of biotech in the suburbs.

Colliers’ Carroll reported that “the suburbs are alive and well”, as the market has added over five million SF of positive absorption since the downturn. There has also been a steady increase in rent growth in the Class A office market, approximately 10 percent since 2009, with new construction in Waltham achieving rents in the low $50s. The Class B market is not faring as well (although there is some rent growth occurring in select markets), with some of the older building stock being slated for repositioning or demolition to make way for senior living, hotel and other non-office uses (including 450,000 SF of properties in Chelmsford). One particularly bright spot is the emergence of biotech in the suburbs.  Citing the enormous amount of commercial, residential, retail and restaurant development underway in the Seaport and other Boston locations, Avison Young’s Perry observed that “Boston is clearly a different city today than it was even five years ago.” The in-migration to the city by firms seeking talent continues, he said, citing the recent relocations by

Citing the enormous amount of commercial, residential, retail and restaurant development underway in the Seaport and other Boston locations, Avison Young’s Perry observed that “Boston is clearly a different city today than it was even five years ago.” The in-migration to the city by firms seeking talent continues, he said, citing the recent relocations by  NKF’s McDonald reported on the industrial market – the newfound darling of investors and developers – noting the transformational effect that Amazon and e-commerce has had on the product type. With 12.8 percent average annual returns to investors over the last five years, industrial has outperformed both retail (12.1) and multifamily (9.9), driven by feverish demand for “last mile” properties located in urban and infill submarkets. That demand has driven rents “way beyond the norms” of what had traditionally been $5 to $6 psf to the “high single digits and low teens” for buildings such as 480 Sprague St. in Dedham, a 234,000 SF warehouse that straddles the Boston line. And warehouse space located within the urban market, such as 202 Southampton St. in the South End (which lacks basics such as air-conditioning), is fetching $20 psf, based solely on location.

NKF’s McDonald reported on the industrial market – the newfound darling of investors and developers – noting the transformational effect that Amazon and e-commerce has had on the product type. With 12.8 percent average annual returns to investors over the last five years, industrial has outperformed both retail (12.1) and multifamily (9.9), driven by feverish demand for “last mile” properties located in urban and infill submarkets. That demand has driven rents “way beyond the norms” of what had traditionally been $5 to $6 psf to the “high single digits and low teens” for buildings such as 480 Sprague St. in Dedham, a 234,000 SF warehouse that straddles the Boston line. And warehouse space located within the urban market, such as 202 Southampton St. in the South End (which lacks basics such as air-conditioning), is fetching $20 psf, based solely on location. HFF’s Sayles addressed the ‘When will the cycle end?’ question early on his presentation. “End of cycle concerns have largely abated,” he reassured the gathering. “Nobody is really talking about that right now, instead, what people’s biggest concern is, ‘If I sell, what am I going to do with that capital?” He expects pricing for assets to remain flat in the near term with cap rates trending downward. Financing for assets is up by 17 percent from Q3 2016 to Q3 2017, but investment sales for that period declined by approximately 8.0 percent as buyers are choosing longer term holds. Sales volume for Boston is expected to be approximately $13 billion for 2017, with foreign capital again accounting for a significant portion of those transactions.

HFF’s Sayles addressed the ‘When will the cycle end?’ question early on his presentation. “End of cycle concerns have largely abated,” he reassured the gathering. “Nobody is really talking about that right now, instead, what people’s biggest concern is, ‘If I sell, what am I going to do with that capital?” He expects pricing for assets to remain flat in the near term with cap rates trending downward. Financing for assets is up by 17 percent from Q3 2016 to Q3 2017, but investment sales for that period declined by approximately 8.0 percent as buyers are choosing longer term holds. Sales volume for Boston is expected to be approximately $13 billion for 2017, with foreign capital again accounting for a significant portion of those transactions. A

A